Against Professionalism!

Professional hierarchies in educational workplaces exist to set groups of workers against each other in service of arbitrary definitions of professional conduct that are imposed by our employers.

Introduction and Methodology

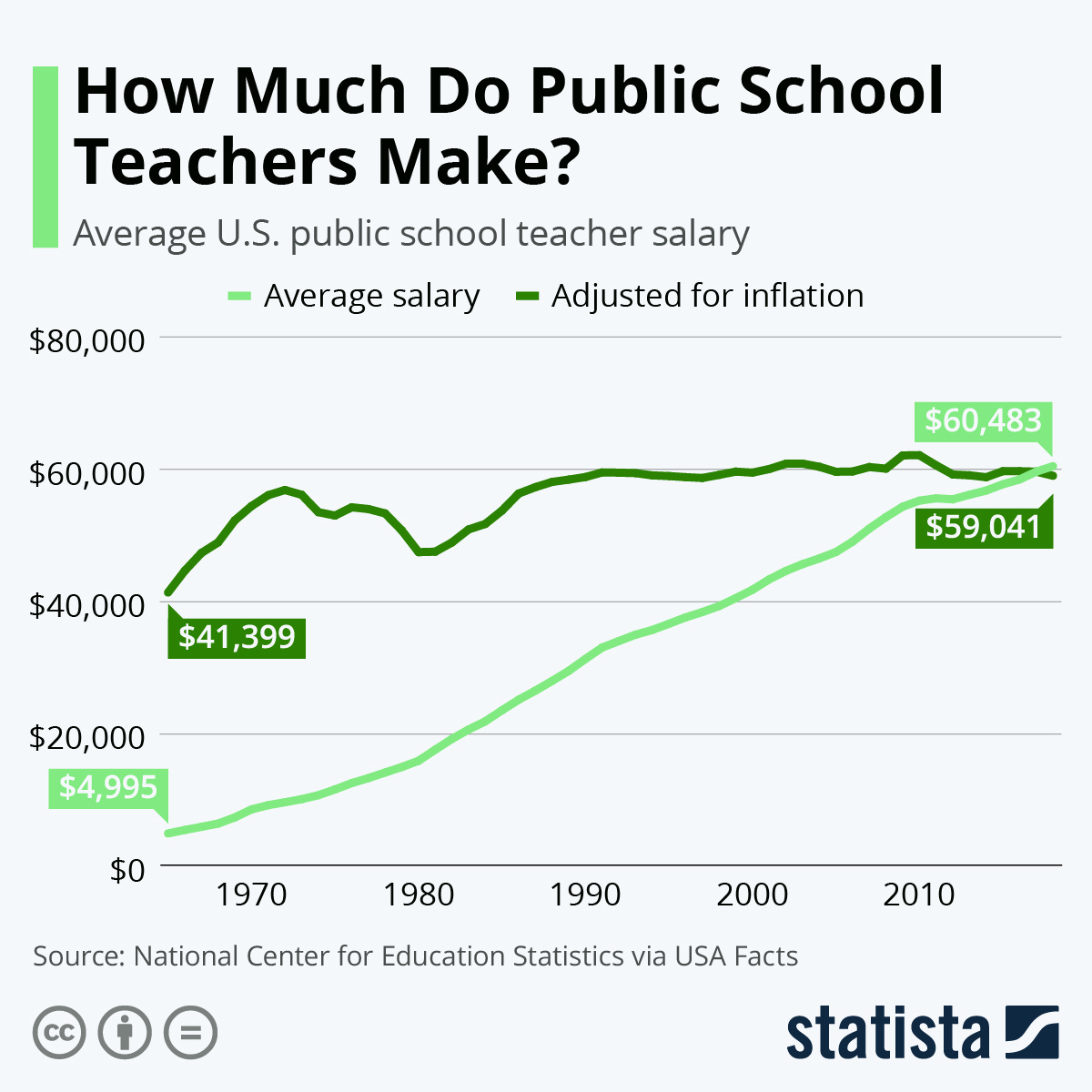

Teachers, specifically lead teachers in charge of specific classrooms, often bemoan their pay and working conditions—and rightfully so. As a lead teacher myself, we are heavily exploited in often dangerous situations. Washington, D.C. ranks in the very top cities in the country for teacher pay. On average, a teacher in this city can expect to start at $67,000 per year. Yet, I often found myself strapped for cash or entirely broke, and even when I save up a little cash, I’m still stuck paycheck to paycheck. Every time I have an unexpected expense, often related to medical care, I start from square one, again. The vast majority of teachers in the United States make significantly less than I do.

Even so, lead teachers occupy a privileged position in relation to many other school staff members. The same is true in every other sector of the industry, such as libraries, museums, daycares, archives, and research labs. Only about half of K-12 school workers are lead teachers. The other half consist of Education Support Professionals (ESPs), assistant teachers, interventionists, food service staff, custodians, counselors, front office workers, behavioral specialists, dedicated aides, related service providers (RSPs), and many other roles essential to educating the successive generations of wonderful young people that grace our lives. Frequently, these workers make less money, and have less access to benefits, than lead teachers. ESPs—commonly referred to as paraprofessionals or paraeducators—generally make about half of what lead teachers make. In most DC charter schools, dedicated aides and substitutes are hired through external staffing agencies for low wages and even less job security than teachers. The ideology of professionalism contributes significantly to this dynamic. Capitalist assumptions that value some skill sets, especially “intellectual” ones, over others is ultimately at the root of professionalism. It’s meant to divide and rule.

We have witnessed the imposition of a “two tier” system in the education industry. There’s no justification for such wide divisions between different job roles. Our goal should be to reduce, and eventually eliminate disparities in pay and access to benefits between education workers. This will require a systemic, revolutionary redistribution of labor and responsibilities in schools, libraries, museums, and other educational facilities. In the meantime, our unions must continue to fight to narrow these hierarchies, especially since teachers’ unions spent much of the second half of the 20th Century entrenching them through craft unionist strategies. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of American teachers’ unions, I wrote an entire essay examining the nuances of this history that you can read.

To be clear, we are not critiquing the term professional or professionalism when used to denote courteous and helpful conduct with coworkers, students, patrons, and community members. Please continue being a pleasant person at work. What we are targeting is professionalism as “constructed from above,” since “it is usually false or selective and used to facilitate occupational change and rationalization. The effects are not the occupational control of work by the practitioners but rather control by the organizational managers and supervisors.”

This text is informed by discussions I’ve had with education workers of diverse job roles and backgrounds—both with coworkers and in communities of educators outside our workplaces. An incomplete list of them includes current or former: paraprofessionals, cafeteria workers, instructional assistants, graduate workers, janitors, preschool teachers, a front office associate at a vocational school, library associates, tutors, special educators, and, of course, lead teachers. There are two primary questions that guided my exploration of this topic:

- How can we work collectively to increase equity and inclusion between all of our coworkers? What role can our unions play?

- Are there any justifications for differences in pay or access to benefits between education workers? What are they?

Our work here is guided by the tools of workers’ inquiry and class composition. The editorial team at the amazing Notes from Below defines workers’ inquiry as “the study of work from the workers’ point of view.” They define class composition as “a theory that allows us to analyze how the working class is organized at this specific point in time by looking at three key factors: the technical, social and political composition of the class.” Technical composition basically translates to what most refer to as the division of labor: What tasks are being carried out and who is carrying them out? What are their working conditions like? Social composition draws our attention to our lives as workers outside the workplace: Who are we? Where do we live? How high is the rent or mortgage payment? What are our family lives like? What oppressive dynamics exist in our communities, such as patriarchal domestic violence? Political composition encompasses how workers collectively organize to exert pressure on employers and political institutions: What struggles between workers and bosses already exist? What professional associations are workers a part of? What unions exist and how militant are they? What egalitarian and democratic political beliefs do workers hold? These tools help us get to the heart of the matter quickly.

Addressing Arguments in favor of Professional Hierarchies

Every educator that I have broached this topic with, including lead teachers, agreed that all education workers deserve a living wage and full access to benefits. Some agreed that professional hierarchies should be eliminated altogether. Most of the best arguments against workplace hierarchies that follow are drawn directly from staff lower on the professional ladders of our industry. The dialogue within our class is ongoing. My goal as a communist is to persuade more of our fellow workers to go beyond traditional craft, trade, and general union strategies1 that exclude half of our coworkers. That said, there are good-faith, legitimate arguments in favor of retaining professional hierarchies that are important to wrestle with.

We live in a time when the professional qualifications of teachers are under attack. With shortages of lead teachers, education “reformers” (privatizers) and their lackeys in local and state governments have taken every opportunity to “deprofessionalize” teaching by lowering the job qualifications needed. Combined with the spread of AI technology and a surplus of college-educated workers with few other job prospects, schools have used the crisis to plug gaps in staffing with less formally qualified workers, such as substitutes and assistant teachers. In Florida, this has gone as far as authorizing school districts to hire military veterans, and even their spouses, as lead classroom teachers. In this context, professionalism is a method to ensure the delivery of a quality education by qualified teachers to every student.

It was two weeks before the school year began. A network administrator paced around the room during an all-staff professional development.

“We’ve adopted curriculum tools that, yes, take the lift of lesson planning off of our ELA teachers.”

There were murmurs of approval from some staff. But at the table next to mine, a dissident voice slipped in among the fray.

“Shameful deprofessionalization,” she said to a colleague sitting next to her, who nodded in agreement.2

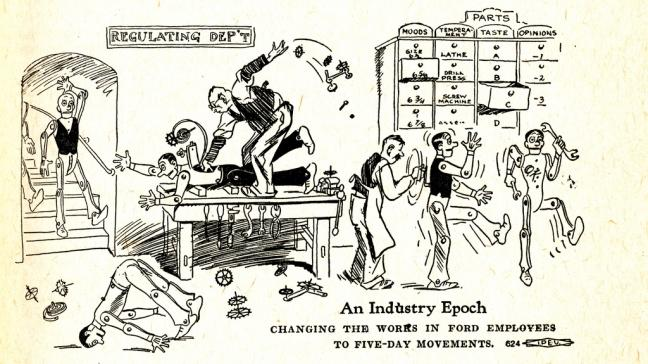

The issue with the term “deprofessionalize” is that it sets the assault on teachers’ working conditions apart from the broader class war against all workers. There is a well understood, somewhat widely known term that is better at describing what teachers are facing: deskilling. As defined by the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, deskilling is “to redesign a job so that less skill is required to carry it out, for example through the introduction of new technology.” Workers across the entire economy have faced deskilling to some extent with the extensive application of digital technology, and now AI.

Another argument in favor of professional hierarchies are the real differences in responsibility levels between job roles. Lead teachers do shoulder a tremendous burden. Anything, and everything, that goes wrong in the classroom can be blamed on the lead teacher—even when they had nothing to do with it. One of the best examples of this is standardized test scores. In many places, teachers can be fired for unsatisfactory test scores, even though those tests do little more than measure a student’s socioeconomic status. This creates tremendous job insecurity for teachers, especially in the charter and private school sectors. Behavioral incidents, too, can come back on the teacher, no matter how large the class size or intensity of the behaviors. Lesson planning and preparation also fall nearly exclusively on the lead teacher, meaning extra hours and work taken home over the weekend. There is also considerably more paperwork, meetings, and captive audience professional developments that lead teachers take on.

However, this argument fails to consider the serious responsibilities shouldered by other members of school staff. It effectively renders them invisible. This mindset renders us blind to the ways our employers are changing the technical composition of the workforce within education to their benefit. The pandemic caused a slow burning teacher training and retention crisis to explode. Understaffing has led to management shoving substitutes, paraprofessionals, teacher assistants, and other staff into de facto lead teacher positions. With no corresponding bump in pay. A friend of ours spent a year working as an instructional assistant at a charter school out west. They spent half of that year as the lead teacher of a class of over twenty middle school students. In my own workplace, there are usually two or three classrooms perpetually taught by teacher assistants or substitutes. During the height of the pandemic chaos it got as high as half. Substitutes and dedicated aides, usually hired through outside staffing agencies, have little to no recourse if their rights are violated. I get the sense that teachers most strongly in support of rigid professional hierarchies work in well funded, well staffed schools where there is less chance of witnessing these exploitative dynamics first hand.

In the case of support staff members such as food service, clerical, and janitorial workers, it is easy to debunk the argument that they have less responsibility than lead teachers. Part of the only reason such a perception exists is because of the way professionalism cordons these staff members off from everyone else. Janitors are on the hook for the safety and habitability of the entire building. They come face to face with all kinds of shit, literal and otherwise. Food service workers require multiple certifications that they can safely handle the food. If a student gets sick, the workers can be held responsible. And don’t you dare tell me that clerical workers such as front office associates have less responsibility than teachers. Schools, and other educational workplaces, would fall apart without these workers. It is insulting to tell these staff members that they deserve lower pay or limited access to real benefits.

Early one morning, as I rode my bike into the parking lot, I waved at one of my coworkers—who was helping unload school meals from the delivery truck. After stepping inside, I ran into him after he’d finished bringing the food to the cafeteria. We chatted, like usual. But then he brought me back into his workspace to show me around. There had recently been an upsurge of animosity between workers and administration.

“You see all this? This is how I do my work. First, I check the temperatures on all the equipment and log it here,” he said while pointing to a chart with at least ten slots for each day.

He brings me to another chart.

“I keep track of all the meals served, eaten, and thrown out, too.”

Next, we go to his computer, where we spend some time looking at photos of his family back in El Salvador. Then, he logged into his account and opened up an application.

“I also order all the food through this portal, and I also block off orders from any days we’re closed,” he says as he rifled through the reams of paperwork he meticulously fills out. Of course, there are regular inspections, and he has to remain diligent about renewing his certifications.

“We like the work, but we feel disrespected and unappreciated, especially because of the pay and the health insurance. The other cafeteria staff have to use medicare.”

On top of all these other responsibilities, he also handles food preparation and delivery. He hasn’t missed a single day of work in his entire seventeen years at this school.

The last argument in favor of retaining professional hierarchies is that teachers, librarians, and similar job roles require higher levels of education to attain, and therefore merit higher pay. Frankly, this seems like a better argument in favor of making higher education free than for paying some people more than others. Tuition represents the biggest hurdle gatekeeping access to many better-paying careers in education. It cannot be overstated how urgent the student loan debt crisis is: this debt is effectively indenturing large parts of the working class. Teachers, in particular, have much higher debt levels than most other occupations requiring a college degree. Not only that, but they also disproportionately struggle to pay them back. Black teachers—unfortunately but unsurprisingly—have the worst of it. To add insult to injury, teachers face an over twenty percent pay penalty compared to other college educated workers.

These are all real, important experiences to factor into any analysis of professional hierarchies in education. But instead of directing our justified anger about our pay and conditions downwards against our “less educated” colleagues, we should organize collectively in ways that combine economic and political demands. Teachers are already leaders within the working class on this front. Bargaining for the Common Good has inspired educators across the world. Using our power to demand free public higher education for all will only strengthen our unity with the rest of the working class, surrounding ourselves with allies in our struggle for a better world for working people.

Without tuition and student loan debt, the need for a pay bump for attaining higher education vanishes. Then, the only thing separating education workers like lead teachers from other coworkers is their level of experience. Obviously, years spent honing your craft in teacher education programs is essential. But is it really right, as a worker fresh out of training, to look over at a preschool teacher with over a decade of experience directly working with students, and to say they deserve less because they lack a degree? I don’t think so. Which brings me to what is, personally, the most offensive professional divide within our industry: the horrendous treatment of early childhood educators.

Early childhood educators face unbearable conditions, and even worse pay. In the District of Columbia, based on 2019 data, early childhood teachers’ “median income was $15.36 for a child care worker versus $33.10 for a kindergarten teacher and $44.16/hour for an elementary school teacher.” Since then, the city has boosted its minimum wage to seventeen dollars an hour, meaning most early childhood educators are now making around (a still horrendous) twenty dollars an hour. There is the Early Childhood Educators Pay Equity Fund, which uses a tax on wealthy District residents to pay out substantial stipends to preschool and daycare teachers. But D.C. is unique in offering that, and it’s likely getting scrapped in the 2025 city budget, over the protests of early childhood educators and their communities. All of this is despicable. To quote from a (meticulously researched and written) letter that one of my students wrote to the mayor:

by cutting funding for early childcare you lower the salaries of a field made up of 94% women and over 40% women of color. Early childcare is the foundation of educated residents and attentive students. Creating a city where early childcare workers are undervalued and underpaid disincentivizes a new generation to join a crucial part of our community.

Some of these workers even have bachelor’s and master’s degrees, but that shouldn’t matter. Whether or not a daycare or preschool teacher has a degree, they bear even greater responsibility than teachers of older grades. Our babies are in their hands. These are, arguably, the most critical developmental years in a person’s entire lifespan. How can we possibly justify pay disparities between us and them? Especially when teachers’ identified pay disparities between primary and secondary school teachers as sexist back in 1897,3 and then spent decades organizing through their unions for a single salary schedule. There must be a different, more equitable, way of structuring our industry.

What can be Done?

The solution is economic democracy, often called industrial democracy. Education workers need collective control of our industry—abolishing management altogether. This piece is not meant to elaborate on the details of what this might look like, institutionally, because that will take a full scale social revolution to accomplish. I want to discuss concrete, actionable steps we can take today, tomorrow, and next year to inch closer to equality between all educators.

Right away, we need to stop identifying ourselves as “professionals.” Whatever our education level, responsibilities, or job titles: we are workers. John Thompson, a former teacher and historian, says it best in his article “Teachers are Workers”.

I just can't see personal or political benefits of trying to get the powerful to see us as professionals. The way we are viewed from above is a small concern in comparison to the way so many other workers and children are treated. Why should we worry about the name given to our position in the team effort known as teaching and learning?

In my experience, the individuals most likely to label us as “professionals” are our managers in administration. If we refuse to trust school, library, and museum administrations on…nearly everything, why should we trust them to correctly identify our real class position in our workplaces? Yes, we are trained, educated, and experienced. So are many other workers across the economy, including within our own industry. Self-identifying as professionals gives us workers at the “top” of these hierarchies a false sense of status. It leads us to break bread with our bosses while distancing ourselves from fellow education workers. It’s the opposite of solidarity. At the same time, the ideology of professionalism justifies the very pay differentials between ourselves and administrators that we recognize as unjust, at least to some degree. We argue that the principal or district leaders shouldn’t be making two, three, or even more times what teachers make, and then we turn and tell staff who we sometimes make twice (or more) as much as that this professional hierarchy is totally fine. It’s time to drop the act and accept that we’re part of the working-class.

When we organize together, we break down these hierarchies and find we have much more in common, both as workers and as human beings, than we ever would have imagined before. Our work—the education of successive generations of human beings—is fundamentally collective and iterative. The same is true of all industries. Pyotr Kropotkin, a prominent anarchist thinker at the turn of the 20th Century, identified this better than anyone besides Marx himself:

Every machine has had the same history – a long record of sleepless nights and of poverty, of disillusions and of joys, of partial improvements discovered by several generations of nameless workers, who have added to the original invention these little nothings, without which the most fertile idea would remain fruitless. More than that: every new invention is a synthesis, the resultant of innumerable inventions which have preceded it in the vast field of mechanics and industry…By what right then can any one whatever appropriate the least morsel of this immense whole and say – This is mine, not yours?

We are already breaking down these boundaries in our day-to-day work, even when we aren’t conscious of it. How many of you have venmo requested a coworker because they used one of your lesson plans? I’m guessing zero. You probably enthusiastically shared it with them when they asked. You might make sure to hold the door for janitorial staff when they are taking out the trash and to strike up conversations with them when you can. Or you’re friends with your assistant teacher and advocate for them during meetings with your shared superiors. This communal spirit is at the heart of what we do. Let’s intentionally extend it outside the bounds of professionalism—and explore new organizational forms that can express solidarity with all of our coworkers.

We also need to be skeptical of the so-called solutions offered by nonprofits such as “professional associations”, which can serve to deflect educators’ grievances and spare energy into groups whose leadership are dominated by our bosses. Take the example of the National Association for Music Education (NAfME). Ostensibly, the association performs a positive function in our industry: advocating for expanded music education programs while providing curricula and advocacy tools to music educators. And I won’t argue that the intentions of those who get involved in associations like NAfME are negative—rather, most share a positive vision of music education and want to work to make it a reality. The problem is the institutional form these educators have chosen and the amount of their time it absorbs. This allows managers and bosses to easily ascend to the top of the organizational hierarchies in these non-profits. For instance, of twenty four people on NAfME’s 2024 National Executive Board, nine were administrators at schools or universities, while six others held positions as arts program supervisors for entire school districts. Notably, twelve spots were held by working music educators, and nearly all of the bosses involved had extensive backgrounds as music educators. But the process of ascending this particular professional hierarchy changes the way an individual thinks about politics and workplace dynamics.

Professional associations like NAfME derail workers’ agitation into a space just as toxic as any other within the non-profit industrial complex (NPIC). According to the anthology The Revolution Will not be Funded, governments and corporations use the NPIC to pacify social movements, shift public money into private hands, launder the reputations of rich donors, and turn community organizing into so many (usually underpaid and exploitative) career tracks. Paying dues and devoting substantial energy to NAfME means those resources, in part, go to executive pay packages ranging from $130,000 to over $200,000. It means time spent on a type of organization that is inherently unable to solve the problems it claims to address. Exemplifying this in NAfME’s case is its close ties to Drum Corps International (DCI) and Bands of America (BOA). These two fellow non-profits have been identified as de facto monopolistic enterprises that destroy locally rooted band cultures and foster environments where abuse runs rampant.

Our time is much better spent in the labor movement than in these company unions.

Thankfully, two real solutions are already on the horizon. In some places, local governments are rolling out teacher apprenticeship programs. Washington, D.C.’s version allows assistant teachers to earn lead teacher certifications, and is housed under the city’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). While the D.C. government, like most of the US government, isn’t really a democracy, it’s at least subjected to some level of public scrutiny. This is a huge improvement over privately controlled alternative teaching certification schemes such as the American Board for Certification of Teacher Excellence or the Relay “Graduate School” of Education. Relay is basically a front for major charter school operators like KIPP, and serves as an indoctrination program in education “reform” (privatization) ideology. If you have any coworkers who are thinking of attending these programs, please steer them away.

It remains to be seen if the political will exists to expand local teacher apprenticeship programs to the entire nation, or if they will be relegated to small scale examples of what could have been. We don’t have time to wait around and find out. Besides, if we want to build independent working class power, we can’t rely on the state, non-profits, or private corporations. It shouldn’t just be up to employers to decide which workers advance and which don’t. Towards this end, those of us in established education unions should advocate investing resources into building in-house professional development programs. Meanwhile, unorganized education workers should seek opportunities to lay the foundation for such programs as we unionize. And we don’t have to do it all ourselves. Partnerships with nonprofits like the Zinn Education Project, which already have established infrastructure for hosting training that workers can use for professional development credit at work, could make this process considerably easier. The Human Restoration Project also has exciting potential. If our employers are allowed to set up sham alternative teaching certification pathways and useless, irrelevant professional developments meant to indoctrinate us, then we have every right to reject them and impose our own solution to the deskilling of education workers.

The second is the rise of wall-to-wall unions of education workers that are explicitly connected to social movements outside the workplace. For nearly a century, teachers have been stuck with unions that reinforce divisions between themselves and other education workers. It wasn’t always this way. During the 1940s and 1950s, conservative factions within teachers’ unions (and the labor movement broadly) purged supporters of social movement unionism, especially leftists of all kinds. They continue to dominate much of the labor movement to this day—though their days appear numbered. New York City’s United Federation of Teachers is the best example: the union represents paraprofessionals, counselors, and most other school workers through separate chapters, but the entrenched leadership regularly betrays them (as well as the teachers). Teachers are clearly dissatisfied with conservative craft union strategy that has left their unions weak and lacking internal democracy. One of the most important dynamics identified by West Virginia and Arizona teachers after their successful 2018 strike was that teacher organizers across the state pushed hard to organize walkouts of all school staff. By standing in solidarity with other school workers, they vastly increased their strength and leverage—shutting down each state’s entire education system.

Since then, this trend of organizing by industry, rather than by job role or job site, has continued to spread among teachers. Earlier this month, education workers in Fairfax County, Virginia overwhelmingly approved representation by the Fairfax Education Unions. It includes over 27,000 school workers, split roughly evenly between instructional and support staff. Also interesting is the fact that the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA) did not compete with one another to represent the whole bargaining unit. Rather, they have agreed to cooperate to represent the workers together. Organized from the bottom up through worker-to-worker conversations, the new union has already displayed real progress towards breaking down professional hierarchies. Bringing all of these workers together provides countless new opportunities to interact, to resolve misunderstandings, and to nuance their perceptions of each other from across all the divides management forces on us. For example, according to interviews with Labor Notes, Ernesto Escalante, a custodian at Crestwood Elementary, has played a key role in bringing custodians and teachers together. He “is excited to advocate for custodian issues at the bargaining table, while working alongside other workers in the school system: ‘It feels good to work with the teachers—to know they have our backs.’” This is especially significant because our employers often rely on the tension between instructional and support staff to break strikes by both.

This is just one recent example. We want to study and spread the word about as many of these as we can analyze. Here is a list of a few more examples:

- The formation of the IWW affiliated wall-to-wall Caliber Workers Union at Caliber Beta Academy charter school in the San Francisco Bay Area.

- Los Angeles teachers effectively went on a solidarity strike with cafeteria workers and won big.

- Minneapolis teachers striking for the common good, including demands for increased paraprofessional pay connected to anti-racist organizing in the city.

- Staff at Mundo Verde Public Charter School form a wall-to-wall union affiliated with AFT in Washington, D.C.

- Museum staff in Philadelphia formed the first wall-to-wall union in a major museum, affiliated with AFSCME.

Most of all, we would love to connect with workers actively involved in these types of struggles. If that describes you, please get in touch! We would love to provide you with a platform to publish, or republish, your reflections on your organizing experiences.

Conclusion

I hope this contribution to the dialogue about professional hierarchies can be useful. It is important that we raise this conversation with our coworkers, in our unions, and through our engagement with our communities. Together, we can narrow these professional hierarchies in our day-to-day struggles as workers—and eventually abolish them.

Ultimately, abolishing these hierarchies would require systemic reorganization of our workplaces that could redistribute roles and responsibilities to place all education workers on the same footing of dignity. This won’t happen overnight, but remember that, sometimes, there are weeks when decades happen. In Oakland in 2022, we caught a brief glimpse of what socialist education might look like when school staff, dockworkers, and community members took over Parker Elementary School and ran it cooperatively for a summer. The school district then hired private security to violently throw them out. Going forward, we hope to see many more examples of these experiments, as soon as possible. There certainly won’t be any shortage of crises or major historical events to fling doors wide open.

Let’s get to work, so that we’re ready to step through them when the time comes.

Thank you for reading! If you are a library, museum, archive, preschool, vocational school, or university/college worker and have any feedback on how I can better include the viewpoints of your locations within the industry, please leave a comment, or get in touch over email or through social media.

Works cited and further reading

1 For a basic explanation of the different types of labor unions, see: A Primer on the Different Types of Labor Unions.

2 As a labor organizer, I keep a daily workplace journal, which has served as an invaluable tool in recalling the specifics of conversations with workers that are years in the past. The quotes you see in this article are drawn from these entries, some newer and some older. Keep in mind that even though I wrote the details of these conversations down within hours of having them, they are not an exact record of what was said.

3 Lyons, John. 2008. Teachers and Reform: Chicago Public Education, 1929-1970. The Working Class in American History. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@gmail.com or over any of our social media.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.