Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 4: Prefigurative

We need a new type of revolutionary unionism to confront capitalism. Revolutionary unions must embody the future societies they strive to create in their present-day organizational forms.

This is part four of an essay series on revolutionary unionist strategy and tactics. Parts one, two, and three are linked below:

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part One: Introduction

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part Two: Dual Power

Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 3: Against Class Collaboration

The rich history of anarchist labor organizing produced the theory and practice of prefiguration.[1] Prefiguration is based on the philosophical stance that means and ends cannot be separated: that the way you choose to achieve your goals will determine what you actually accomplish. Past revolutionaries often expressed this idea with the phrase “we are building the new world in the ruins of the old.” Revolutionary unions are aware of this and act accordingly. At every turn, revolutionary unionists should embody today the societal relations we aim for in the future, when capitalism is no more. When we act prefiguratively, we emphasize building the skeletal and nervous systems of a new, liberated, social body. Then, when the revolution comes, we are already prepared to seize the moment during a situation of dual power and achieve a true transformation of society.

Prefiguration is an excellent framework for understanding how social structures shape individual and collective actions—which helps take the focus off of an individual's personal character and intentions. Revolutionary unions recognize that all individuals and groups are flawed, and take steps to develop egalitarian systems that facilitate working class self-leadership. Our institutions need to horizontally distribute power and decision-making as much as possible. Here, we can learn from Errico Malatesta, a militant of the international anarchist workers’ movement of the early 20th Century, and one of the first to articulate a theory of prefiguration. He advocated a “government by everybody” that is “no longer a government in the authoritarian, historical and practical sense of the word.”

Bickering contests dissecting the character and intentions of past revolutionaries and labor leaders are counterproductive. These sectarian debates distract us from the real work of building towards revolution. We can collectively deconstruct these debates by analyzing the concrete effects of decisions and structures instead. Commenting on the Bolsheviks in a 1919 letter, Malatesta wrote that they:

are merely marxists who have remained honest, conscientious marxists, unlike their teachers and models, the likes of Guesde, Plekhanov, Hyndman, Scheidemann, Noske, etc., [the prominent social democratic leaders of their era] whose fate you know. We respect their sincerity, we admire their energy, but, just as we have never seen eye to eye with them in theoretical matters, so we could not align ourselves with them when they make the transition from theory to practice.

Malatesta demonstrated the ability to engage in principled, nuanced, and respectful criticisms of the political tendencies he disagreed with.

If someone is a worker and willing to respect members of all backgrounds, they should be welcome. Forty percent of the teachers who walked out for the Red for Ed strikes of 2018 voted for Trump in the 2016 election.[2] The revolutionary union movement encourages plurality of thought while engaging in collective education. Our present choices about how to handle disagreement and conflict—both internally and between organizations—will determine the type of society we replace capitalism with. We must use internal political education and persuasion to help workers begin to overcome the baggage we all carry under capitalism. “Beyond ‘Fuck You: An organizer’s approach to confronting hateful language at work” provides a model of what this looks like in one-on-one and small group settings. As we grow, we have to incorporate this model into all of our organizational infrastructure. Whatever our other disagreements about politics are, we must all commit to structuring our unions directly democratically.

Here we must raise a criticism of those who pursue democratic centralist lines of organization. Democratic centralism originates with the Bolsheviks, representing an attempt to fuse democratic deliberation with highly centralized authority.[3] It’s true that “when leadership is not openly acknowledged, it operates unofficially and informally, so that the members have no effective way to hold it responsible”. Feminist organizers termed this phenomenon the “tyranny of structurelessness.” Informal cliques of power brokers are corrosive to democracy. We agree with these critiques, and also understand the need for maximum unity among the workers, but democratic centralism fails to solve the problem. By centering a cadre of leaders that are supposed to be in unity with the working masses, organizational hierarchies can easily become entrenched. This practice, this means to an end, usually leads to deepening divisions between the rank-and-file and the leadership that reproduce capitalist social relations inside our organizations.

While proponents of democratic centralism acknowledge the tension between democracy and central authority, they stress the “crucial role of organizational leadership”. This makes them, in their own words, vulnerable to “commandism” and “the development of personality cults” whenever leadership fails to properly synthesize their own “theoretical and practical experience and mature political judgment” with the desires and needs of the membership, as well as those of the broader proletariat. Intentions matter little here, since embedding a hierarchy between leadership and membership will lead to the erosion of internal democracy, with the organization increasingly dominated by cliques distant from the experiences of regular working people. The history of most communist parties and trade unions should teach us that a democratic centralist line rarely remains democratic in any meaningful way. Democratic centralism, then, trends towards a “monolithic unity” of action that stifles the opinions of an electoral minority. Full consensus on contentious issues within a revolutionary union is impossible, so decisions by simple majority or supermajority will be necessary most of the time. The problem begins when “unity of action” binds the right of the minority to protest and to act in an autonomous manner.

Prefiguration as an organizational philosophy, on the other hand, opens space for us to critique past social and revolutionary movements without picking apart specific individuals who many of our fellow workers might admire. Let’s examine two concrete examples from within the teacher union movement. New York City’s United Federation of Teachers (UFT) has been dominated by the Unity Caucus since the union’s formal organization in the 1960s.[4] Its leadership constantly undermines any attempt at dissent or independent action by sections of the membership. When UFT Education Support Professionals (ESPs) formed the Fix Para Pay slate and elected a dissident Chapter Leader, Migda Rodriguez, Unity leadership effectively made it impossible for her to do her job. Our revolutionary union movement must embrace open dissent. Especially after the official vote has been taken.

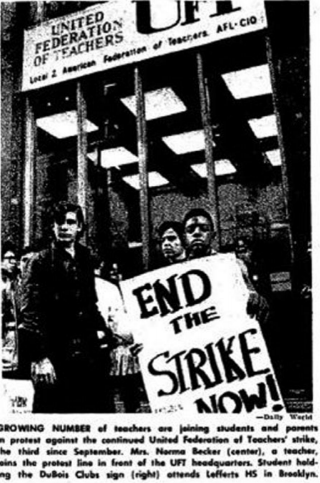

It is tempting to hide our internal disagreements to present a favorable view of the union to the public, but setting up a cadre of leaders that exists above the membership prefigures a hierarchical organization that reproduces capitalist social relations. Prefiguration helps us understand that this false unity is counterproductive. Only through a combination of public-facing and internal deliberation and dissent can we give birth to truly revolutionary unions. The contrasting approaches of the UFT and the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) from 1968 to 1971 provides an illuminating example. In 1968, the UFT—under the ironclad leadership of Albert Shanker—launched the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Strike against an experiment in community control by Black neighborhoods over their local schools. Regarded by Black New Yorkers, most Black teachers, and leftist teacher unionists as a “hate strike”[5], the UFT won at the cost of the trust of the families and students they served.[6]

In Chicago, the CTU made a similar mistake, also in 1968, by ignoring the demands of the significant Black minority of the union’s membership and the wider Black Community. Nearly half of Black teachers crossed the picket line. These members were maligned as traitors and scabs undermining the strike by expressing their discontent with the white majority establishment of the CTU. A revolutionary unionist perspective emphasizes how publicly registering their anger with the union laid the foundation for lasting change. Groups such as Concerned Parents, Operation Breadbasket, and the Black Teachers Caucus in the CTU reformed it and Chicago Public Schools. These Black led groups exercised a leverage in the CTU that Black people could not wield within the UFT. With concrete power inside the union and militant community confrontations with white school administrators, the police, and white teachers over racism, the CTU and Board of Education hired black teachers, added Black history and culture courses, and gradually certified Black substitute teachers. Leaders like Timuel Black and hundreds of Black teachers prevented a potentially fatal split within the CTU and raised the percentage of Black teachers and administrators to significant minorities or majorities by 1980. When the CTU struck again in 1971, Black teachers proved overwhelmingly supportive.[7] It is no coincidence that the UFT is still dominated by an anemic, anti-democratic leadership while the CTU has become a model for unions everywhere.

A revolutionary union movement must be led directly by its membership. How can we cultivate this working class self-leadership on an organizational level?

That’s all for this week! Check back next week for part 5, on the need for revolutionary unions to be democratic and inclusive.

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.

Baker, Zoe. 2023. Means and Ends: The Revolutionary Practice of Anarchism in Europe and the United States. Chico CA: AK Press. ↩︎

Blanc, Eric. 2019. Red State Revolt: The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics. Jacobin Series. New York City: Verso Books. ↩︎

For a detailed explanation and analysis of democratic centralism from a supportive point of view, see “Confronting Reality/Learning from the History of Our Movement” (1981) by the Bay Area Socialist Organizing Committee. ↩︎

Shelton, Jon. 2017. Teacher Strike! Public Education and the Making of a New American Political Order. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ↩︎

Buffett, N.P. 2019. “Crossing the Line: High School Student Activism, the New York High School Student Union, and the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville Teachers’ Strike.” Journal of Urban History 45:1212–36. ↩︎

Goldstein, Dana. 2014. The Teacher Wars: The History of America’s Most Embattled Profession. First Edition. New York: Anchor Books. ↩︎

For a detailed analysis of events in Chicago, see: Lyons, John. 2008. Teachers and Reform: Chicago Public Education, 1929-1970. The Working Class in American History. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ↩︎