Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 6: Militant

We need a revolutionary union movement to confront the power of the employing class. Revolutionary unions must embrace militant, class struggle strategies and tactics to win.

You are reading part six of a series on revolutionary unionist strategy and tactics. If you have not read the previous entries, you can start at part one here:

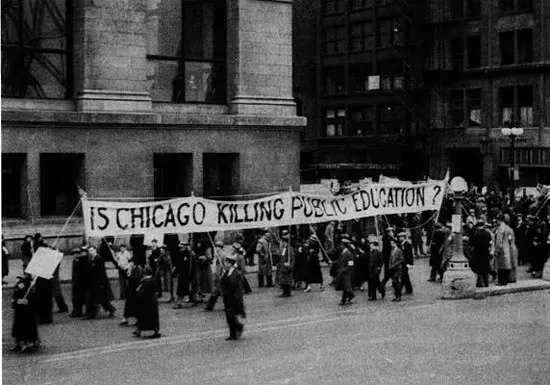

A revolutionary union movement must reject service models of labor organizing that position workers as the beneficiaries of certain exclusive perks. Not only does this make it easy to paint the labor movement as a special interest group separate from the rest of the working class, it does little to build real worker power. Collective direct action is the only way to demonstrate that the means of production are in our hands, and that without our labor nothing in society can function. Direct action is also an opportunity for shared learning that prepares us for the conquest of the relations of production during dual power and the transition out of capitalism. We come to understand that we are not helpless cogs in the machine, but the movers of the immense machines that we can paralyze, transform, or smash if we so choose. More, we hone our ability to cooperate and empower ourselves to take greater control over our own lives, filling us with the confidence to demand the dignity and fulfillment we deserve.

Our revolutionary unions must take bold initiative when other unions can’t or won’t. In the battles of the class war when we confront our employers head on, a revolutionary union movement is the vanguard formation. We take the fight to the bosses and their enforcers—giving and taking the hardest hits to open space for the entire proletariat to struggle autonomously for its own interests. In an increasingly repressive political and legal environment, we can look to our ancestors’ for guidance. The AngryWorkers political collective argues that the strikes preceding WWII “repeatedly opened up spaces for other ‘poor people’ and offered opportunities to fight for their interests even without their own productive power, to break out of the loneliness of courtrooms and the clutches of a paternalistic administration of poverty”.

We are undeterred from going beyond wages and conditions to fight wider political battles through collective direct action, as well. From this point of view, a contract is a mere piece of paper. Bosses break the terms of labor contracts all the time. The right to strike is in our hands, no matter what the law or a contract says. Obviously, that doesn’t mean we should be reckless. People’s lives are on the line. But a revolutionary union that is afraid to break labor law is not a revolutionary union at all. We cannot prioritize our treasuries or liberal notions of respectability over direct action. When it comes to maintaining the class hierarchy, capitalists are always willing to set the law aside. Fascism, for example, represents the logical conclusion of capitalist dictatorship in the workplace and colonialism. Joe Burns argues that asserting the right to strike requires “a wholesale repudiation of existing labor law, a rejection of employer property rights, and a commitment to organize the key sectors of the economy through militant tactics”. It is the responsibility of a revolutionary union movement to discern these strategic needs and to democratically determine what direct actions to take.

Relying on the legal system to tip the balance of power in our favor is a dire mistake, even when it goes our way in the short term. A revealing case study is the outcome of the 1974 Hortonville Teachers’ Strike, a labor struggle in a rural Wisconsin town. Taking place in the context of the backlash by the “Silent Majority” to the Civil Rights, Black Power, and anti-War Movements, the strike turned violent. Unemployed men formed vigilante squads to harass and attack strikers and their supporters. The striking teachers sought support from the state NEA affiliate, the Wisconsin Educational Association Council (WEAC), which called for a vote to approve a one day state-wide sympathy strike with the Hortonville teachers. When the vote failed badly, the WEAC turned to legislative action. They succeeded in getting a law passed that provided teachers’ unions with “compulsory interest arbitration” that improved their ability to secure contracts without striking. However, Eleni Schirmer, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, argues that “this calculation…it failed to develop stronger forms of labour organising – workers’ power to…develop widespread solidarity with other workers and community members to transcend the narrow and economic interests of employers, be they businessmen or administrators”.

Today, labor law is even weaker than it was back then. And so far, all attempts to significantly reform labor law have failed. Using whatever advantages we have under existing labor law is fine, but pinning our hopes as a movement on changing the law would be the death of the labor movement. Strategies that rely on legal fixes are entirely at the mercy of who the president has appointed to sit on the National Labor Relations Board. A revolutionary union refuses to wait until the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act is passed to take action. We have no illusions about the law, which we know will always side with the bosses and against the workers.

Whenever possible, revolutionary unions should even go beyond demanding changes from economic and political authorities. Instead, we enforce our needs through direct action at the point of production. The early IWW provides a concrete example of what this might look like in practice. In 1917, among the forests of the Pacific Northwest, the IWW’s Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) led a strike for the eight hour workday. Two months into the strike, the bosses continued to hold out and the US military was moving to repress it—lumber was essential for WWI production—so workers voted to “strike on the job”. James Rowan, an IWW lumberjack and “job strike” participant, describes this tactic at length in his book The IWW in the Lumber Industry:

When the strikers returned to the job, instead of doing a day's work as formerly, they would "Hoosier up", that is, work like green farmer boys who had never seen the woods before. Perhaps they would refuse to work more than eight hours, or perhaps stay on the job ten hours, for a few days, killing time. When they had a few days pay, they agreed among themselves to work eight hours and then quit. At four o'clock some one would blow the whistle on the donkey engine, or at some other pre-arranged signal, they would all quit work and go to camp. The usual result of this was that the whole crew would be discharged. In a few days the boss would get a new crew, and they would use the same tactics. Meantime the first crew was repeating the performance in some other camp. When a boss had a crew, he got practically no work out of them, and what little he did get, was done in a way that was the reverse of profitable. A foreman always thought he had the worst crew in the world, until he got the next. The job strikers achieved the height of inefficiency on the job, while retaining their usual efficiency in the cook house at meal times.

In most camps the job strike was varied at times by the intermittent strike, the men walking off the job without warning, and going to work in other camps. This added to the confusion of the bosses, as they never knew what to expect.

These tactics had never been used on such an extensive scale in the United States. The companies could not meet them. All over the Northwest the lumber industry was in a state of disorganization and chaos. There was no hope of breaking this kind of a strike by starvation; much against their will the companies were forced to run the commissary department of the strike.

Because of the previous “off the job” strike, the lumber companies had no reserves left to sell off, either. And the war economy meant that demand was extremely high. The Lumber Trust had no choice but to officially enact the eight hour work day across most of the region. In an era of endless war, the job strike is a tactic that should be in the arsenal of every revolutionary labor union.

Thanks for reading! If you're interested in reading the next part of the series, you can find it here:

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.