Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part 7: Heterodox Strategy and Tactics

A revolutionary union movement must find a way to overcome "the syndicalist cycle." It must navigate the class struggle in a fluid, adaptable way to outflank capital.

This is part seven of a series analyzing revolutionary union strategy and tactics. If you have not read the previous entries, you can start at part one here:

In the class war with the employing class, workers must be infinitely adaptable and flexible. Like water, we must be capable of flowing smoothly and evenly in one moment, then cascading in a torrent the next. Revolutionary unions are organized cores of revolutionary workers that provide a vehicle for all willing workers to use in their struggles for a better world. When a group of workers decides to go on the attack—or when they need to defend themselves from capitalist aggression—they can do so with the full weight of the union behind them. A revolutionary union does not back down in the face of intense class struggle. It escalates by widening the conflict, bringing in more and more workers continually, mimicking the expansive, cancerous logic of capital, but flipping it against itself.

The modern IWW calls its organizing philosophy “solidarity unionism,” which is defined in the union’s Organizer Training 101 as direct, democratic, caring, and industrial. As an approach, it de-emphasizes the importance of signing formal collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) and pursuing legal remedies for union busting. Many IWW members advocate eschewing union contracts altogether and relying solely on informal workplace organizing committees. An immense swathe of the economy falls outside the purview of the NLRB, such as “public-sector employees…,agricultural and domestic workers, independent contractors, workers employed by a parent or spouse, employees of air and rail carriers covered by the Railway Labor Act,” and private religious school workers. At these workplaces, “pure” solidarity unionism is, in fact, the best approach, and one that no other union in the US can replicate. With no legal mechanism to enforce CBAs, it makes sense to rely entirely on informal workplace organizing committees supported by a wider union.

We think this is a dogmatic approach when applied too broadly. It adapts poorly to labor organizing in the rest of the economy. Pure solidarity unionism in these industries, after two decades of testing, has mostly produced ephemeral workplace organizing committees, with concrete, long-term impacts equally ephemeral.

Meanwhile, IWW branches that take a hybrid, heterodox approach to CBAs have a far higher rate of lasting campaigns. These branches help campaigns sign CBAs if the workers want to, but treat these contracts as mere scraps of paper that provide a baseline of institutional stability for the workers in the union, and nothing more. In Portland, Oregon, workers at the Burgerville chain organized with the IWW and achieved the first fast food union contract in US history. Despite containing a “no-strike clause,” workers have gone on strike over a dozen times in just the last few years. We should avoid no-strike clauses whenever we can, since they restrict our right to use our most powerful weapon, the strike. Ultimately, however, these agreements are pieces of paper that a revolutionary union should rip to shreds whenever they get in our way. Contract negotiations paired with direct action are a perfect time to assert our principles to transform the de facto, day-to-day enforcement of labor law. Chicago’s Mobile Rail union successfully convinced the NLRB to recognize the IWW’s general opposition to no-strike clauses as a fundamental principle of the union it could insist during negotiations.

Moving south, the San Francisco Bay Area General Membership Branch (GMB) of the IWW has the oldest continuous workplace organizing campaigns in the entire modern IWW—all of which have formal CBAs. In addition, the branch keeps racking up new victories with their heterodox approach to contracts. In July 2023, the branch organized three Peet’s Coffee and Tea locations—spawning the Peet’s Labor Union, which has since unionized a fourth Bay Area location as well as a fifth in Portland, Oregon. During that same timespan of less than two years, several workplace unions at bookshops, a recycling center, and an environmental non-profit affiliated with the Bay Area IWW. Most notably, the branch has an ongoing, wall-to-wall union campaign—the Caliber Workers Union—at a regional charter school network with multiple campuses and over 200 employees. They are currently helping the workers fight for their first union contract.

We could overcome the “syndicalist cycle” by incorporating common moderate union practices like contracts in small doses, while never compromising on our revolutionary vision for the future. This approach would inoculate us against abandoning our revolutionary principles. By engaging with these practices we must simultaneously act to transform them. Union contracts normally can only cover wages, benefits, and hours. Organized worker power can change this. Teacher unions in particular, but now also the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA), are setting precedent for things like housing, AI, funding levels, and more to be struggled over even in formal negotiations. The cooperation of the Civil Rights Movement and the labor movement in the 20th Century taught us that the law is not set in stone, and that we can change legal precedent through our organized struggles.

Bargaining for the Common Good is an approach that unites the direct action of solidarity unionism with the wider political and economic struggles of our communities. Originally formulated by militants of the CTU during their landmark 2012 strike, the union has continued to escalate the pressure against the legal frameworks designed to contain them. The CTU is now inviting community members into contract bargaining sessions, bringing the wider working class directly into confrontation with the employing class in education. Revolutionary unions should pack contract negotiations with as many members and community members as can fit safely in the bargaining locations. Then, when we have won what we need, we spend the duration of the contract taking direct action to achieve greater shop floor control and improvements to working conditions. When it’s time to bargain the next contract, we fight to codify all of our de facto gains in the new CBA. Capital is endlessly adaptive to our resistance to its rule. We think that these heterodox approaches to contract negotiations and collective bargaining represent a more practically revolutionary stance than turning our backs on them entirely.

At the same time, we must become ungovernable. Burgeoning revolutionary unions intentionally import insurrection into the workplace. That means launching illegal and wildcat strikes. The beloved 2018 Red for Ed education strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona (and beyond) were all illegal and nearly entirely against the will of their union bureaucracies within the AFT and NEA.1 It also involves unifying our industrial battles with the insurrections in the streets. After the failure of the Detroit Rebellion of 1968, Black auto workers decided to take the lessons of the uprising and bring them to the point of production in their own workplaces. This was the genesis of the LRBW. History provides no shortage of other inspirational examples.

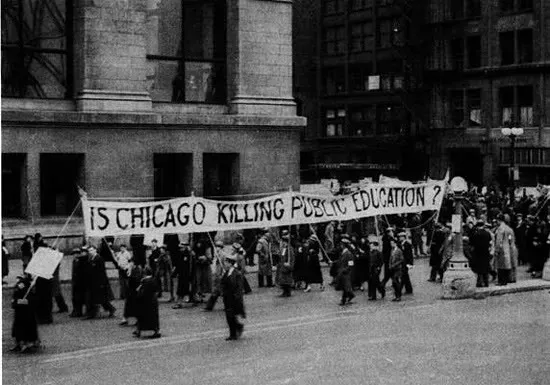

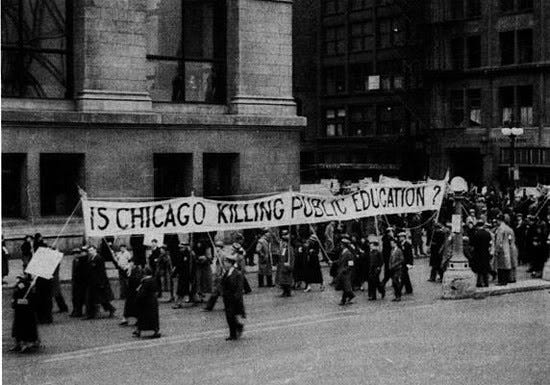

In the deepest depths of the Great Depression in 1934, Chicago teachers rioted, looting banks and beating mounted police with textbooks.2 That same year, the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike saw “a major battle between strikers and police…in the central market area.” Knowing that the police would try to break their strike, the union placed 600 strikers in the nearby AFL headquarters. When the police arrived, these picketers “emerged and routed the police and deputies in hand-to-hand combat. Over thirty cops went to the hospital. No pickets were arrested.”

Teachers in Oaxaca, Mexico, took it several steps further in 2006 when police attempted to evict their annual strike camp—which occupied the city’s central plaza. After the teachers repelled the cops’ first assault, the city’s entire disproportionately indigenous working class mobilized and expelled them from Oaxaca entirely. For nearly a year, Oaxaca was governed by community and worker assemblies until federal Mexican troops retook the city.3 Even then, the movement survived and has continued to evolve. Ten years later, in Catalonia, revolutionary unions, including the modern CNT, called a general strike in response to police repression of Catalan separatist protests and electoral shenanigans by the central Spanish government. Reformist unions, surprisingly, followed their lead. Police forces were forced to retreat across much of the region. Revolutionary unions effectively tread a fine line by advocating against Catalonian nationalism while articulating working class rage against those who would try to crush the self-determination of their people. The “ability for the CNT and the other radical unions to take leadership of the situation was based on their very patient day-to-day organizing in workplaces and communities—as revolutionaries”.

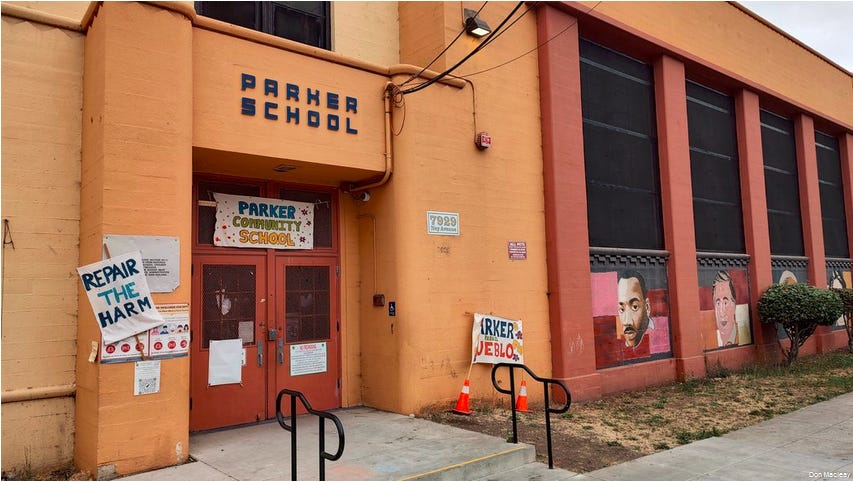

Closer to home, an informal coalition of school workers from the Oakland Education Association (OES) and the Oakland International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) joined forces to oppose gentrification and school privatization in their city. Their alliance culminated in the occupation of Parker Elementary School, which had just been closed in order to make way for the city to open even more charter schools. Reopened as a community school for the summer of 2022, the building became a hub for neighborhood organizing and truly democratic education. Until the city hired private security to forcefully evict teachers, dockworkers, and their children, that is.

The syndicalist union SI Cobas in Italy uses mobs of students and left-wing activists from outside the workplace to set up blockades of workplaces during strikes of small groups of migrant workers in logistics. This tactic enables precariously employed migrant workers to leverage collective power against their employers until they’ve built majority support in the workplace. Combining such insurrectionary tactics with anti-imperialist organizing would represent a major strategic innovation and bring the abolition of the Military-Industrial Complex into view. Palestine Action is an anti-imperialist, anti-war group that targets multinational weapons manufacturers—specifically those used by the Israeli regime against the Palestinians, like Elbit Systems—for blockades, occupations, and sabotage. With the cooperation of revolutionary unions and organizations like Palestine Action comes the potential of the occupation of weapons factories and their transformation into sites for the production of socially useful goods. Even starting with just one or two conscientious workers could be enough of a foothold to spread the struggle through a whole plant. In Florence, Italy the ex-GKN Factory Collective helped conjure a vision of what this might look like when it occupied its workplace after the employer closed the facility. Since then, they have been fighting to transform the plant into a public hub for sustainable mobility.

Even though most of these struggles ultimately ended in failure, they represent the seeds of a future revolutionary union movement that can overcome the employers and the state. They prove that imposing insurrectionary tactics such as occupations, sabotage, and blockades onto our bosses work in our favor. Let them cry about it, as long as they concede to all of our demands. If they don’t, we’ll take that power from them and run them out of town.

By demolishing the legal framework of narrow trade unionism, we bring the fight to a broader confrontation with the economic and political powers who rule over us. Workers are already moving in this more militant, potentially revolutionary direction. Just looking at the education industry: illegal strikes, street protests, occupations of school workplaces, wall-to-wall unionism, bargaining for the common good, organizing the unorganized, borderline solidarity strikes, and political strikes all point some ways forward. Meanwhile, workers are clearly increasingly unsatisfied with the conservative bent of most mainstream unions. All revolutionary unions should encourage members employed in already unionized workplaces to build worker power independent of the leadership.

Part eight will be up next week! Be sure to check back, because we still (somehow) have more to say!

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.