Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part One: Introduction

We need a new, revolutionary type of unionism that can confront the power of the employing class. Our new essay series examines the traits revolutionary unions must possess to measure up to the task.

The working class today stands at a crossroads amid deepening, interlocking crises. With education workers leading the way, the labor movement is in the early stages of revitalization—the awakening of a sleeping giant. For all their admirable successes, though, the prominent trade unions themselves have historically played a key role in constructing divisions between themselves and the lower strata of the proletariat. The most obvious example of this is the US craft union movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries embodied by the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which excluded “unskilled” workers, segregated its Black members, tried to keep women out of the workforce, and lobbied for anti-immigrant legislation (while more than half of the members were themselves immigrants). Christian Frings with the German leftist newspaper analyse & kritik dives deeper into this history:

Parallel to the introduction of social insurance, the establishment and legal protection of trade unions developed as the representation exclusively of this part of the proletariat, the “wage laborers”, who can proudly point out that they live from “their own hands’ honest work”. In the early days of modern mass trade unions after the largely spontaneous Europe-wide strike wave between 1889 and 1891, they were referred to as “strike prevention associations” by more critical minds in the workers’ movement. This was because the monopoly granted to them by the state and capital on the form of struggle of the strike in conjunction with peacemaking collective agreements was intended to put an end to the wild goings-on of work stoppages, factory occupations, sabotage and riots on the streets. Although it took two world wars, fascism and the Cold War for this model to become effectively established in the Global North, it still works quite well today with the very moderate use of strikes.

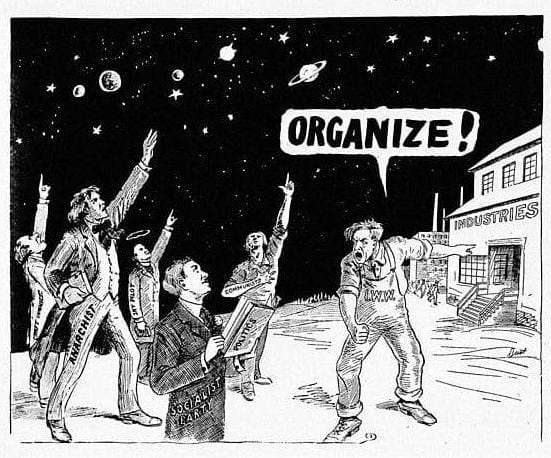

In the US, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) emerged in 1905 in opposition to these exclusionary unions and is often mentioned alongside the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) as a quintessential example of revolutionary unionism. But these unions were usually crushed to earth during WWII and the Cold War—the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), for example, was strong-armed into expelling communist led locals in 1941. The IWW, already hit hard in the First Red Scare, had membership in its organization criminalized during the Second Red Scare. In Spain, the CNT was outlawed during the tenure of the fascist regime of Francisco Franco.

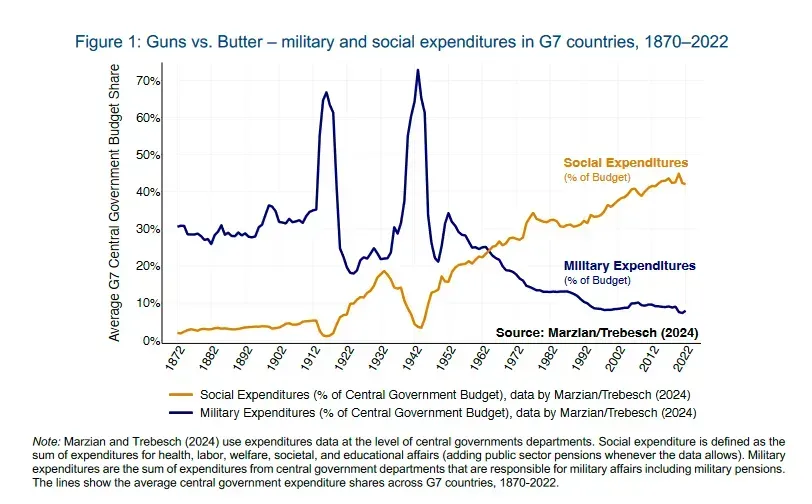

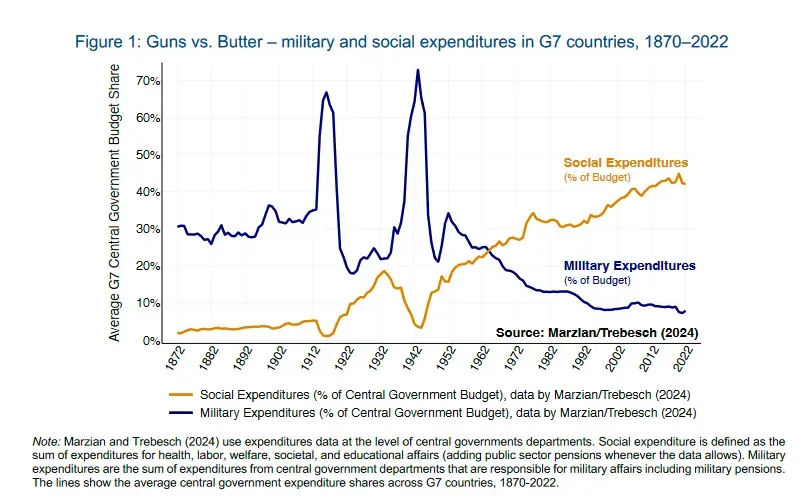

Simultaneously, the governments of the Global North contained proletarian resistance by investing in social welfare and encouraging the growth of trade unions with moderate and conservative strategies—often labeled as business unions. Some workers attempted to break out of their containers starting in the late 1960s—such as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in the US, the workers’ councils in Italy, and the insurgent workers of May ‘68 in France. The ruling class unleashed savage repression and economic reforms that defeated these movements, scattering revolutionary workers. Moderate union leaders and staffers were totally unprepared for the Neoliberal war of attrition that has destroyed most of the labor movement.

The remnants of the old labor movement are often conservative and complicit in atrocities committed by our military-industrial complex. A massive portion of the US labor movement was built during WWII at munitions factories. Throughout the entire Cold War, the AFL, and then AFL-CIO, collaborated with the CIA in the overthrow of democratically elected governments in Latin America and beyond. Unsurprisingly, these union leaders who were willing to sell the global working class down the river then turned around and did it to their own memberships. Even today, most union leaders in this country, with the exception of some like Shawn Fain, demonstrate little regard for the rank-and-file.

So far, the response to union conservativeness and weakness on the shop floor from the 1980s until today has been what Joe Burns, author of Class Struggle Unionism, calls “labor liberalism.” Unions such as the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and workers’ centers are prominent types of labor liberal organizations. They were a more progressive response to business unionism, but remain ultimately fixated on “choreographed” labor actions like one day strikes and staff heavy organizing that maintains the containment of proletarian struggle. Rather than a step forward, labor liberalism represented a failed compromise between business unionism and revolutionary unionism.

Both remain insufficient vehicles for the revolutionary sections of the proletariat. We need an explicitly revolutionary union movement that can take the offensive against capital, one that can rupture the political and legal structures that act to stifle proletarian resistance. Accomplishing this will take situating ourselves within an ecosystem of proletarian organization that broadly encompasses three categories: production, insurrection, and reformation. There are many useful models from the past we can draw from, but for all the continuities between now and the historical situations that birthed the revolutionary union movements of the past—such as the early IWW, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), or Swedish Workers’ Central Organization (SAC)—there are just as many differences. Our task, as those of us who would call ourselves revolutionary unionists, is to articulate a concrete, specific vision of revolutionary union strategy that wins the support of large masses of the working class.

Our aim is to define some key guiding characteristics that a union must possess to be part of a revolutionary union movement. In addition, we will try to sketch a broad strategy that can transcend the pitfalls previous generations of revolutionary union movements have fallen into. At the front of our minds is what might be called the “syndicalist cycle.” This describes the tendency of revolutionary unions to get marginalized within the labor movement in times of labor peace between workers and capital, like the Postwar “Golden Age of Capitalism.” Revolutionary unions that ride the wave of reform in order to stay relevant then begin to degenerate into business and labor liberal union practices. The SAC and French General Confederation of Labor (CGT) are emblematic of this cycle. Somehow, we must overcome this dilemma and build a revolutionary union movement that can do both. In Guerilla Warfare, one of the three main lessons of the Cuban Revolution that Ernesto Che Guevara identifies is that “It is not necessary to wait until all conditions for making revolution exist; the insurrection can create them.” Whatever his individual flaws, perhaps this conclusion of his can guide us.

Hopefully, this can serve as the roughest of drafts for a blueprint to organize revolutionary unions—or transform existing reformist unions into revolutionary ones. This text is the result of conversations raised within the labor movement and various worker-centered communities, such as: union bodies of active organizers within the IWW, individual labor organizers in various mainstream unions, internet forums for union workers, radical political collectives, and social spaces for education workers. This text is also meant to address key questions posed by Class Struggle Unionism: “what type of workers’ movement would it take to blockade workplaces, violate injunctions, and engage in outlawed solidarity tactics? How can we pick some battles and move them beyond the existing system? Can this be done in existing unions or will it require new ones, or a combination of both?”

We think the answer is a revolutionary union movement. With this in mind, we posed three questions:

- Do we need a revolutionary union movement? What would a revolutionary union movement look like? How can we build one?

- How can we build unions that can effectively and democratically channel these already existing, escalating working class struggles towards revolutionary action? Action that the employing class can’t redirect towards other ends.

- How can we articulate a concrete, specific vision of revolutionary union strategy that really captures the hearts and minds of masses of working people? What administrative capacity do we already have to accomplish this, and what capacity do we need to build? How do we sustainably mobilize our resources in this direction?

To the questions of whether or not we need a revolutionary union movement: the answer was overwhelmingly yes. Now, we offer up this text that weaves together our thoughts for critique, discussion, and circulation among worker-organizers in the IWW and beyond. We must emphasize that this text represents the beginning, not the end, of the conversation.

Part two comes out next week! If you found this essay useful, make sure to check back here, because we’ve got a lot more to say!

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.