Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement, Part Two: Dual Power

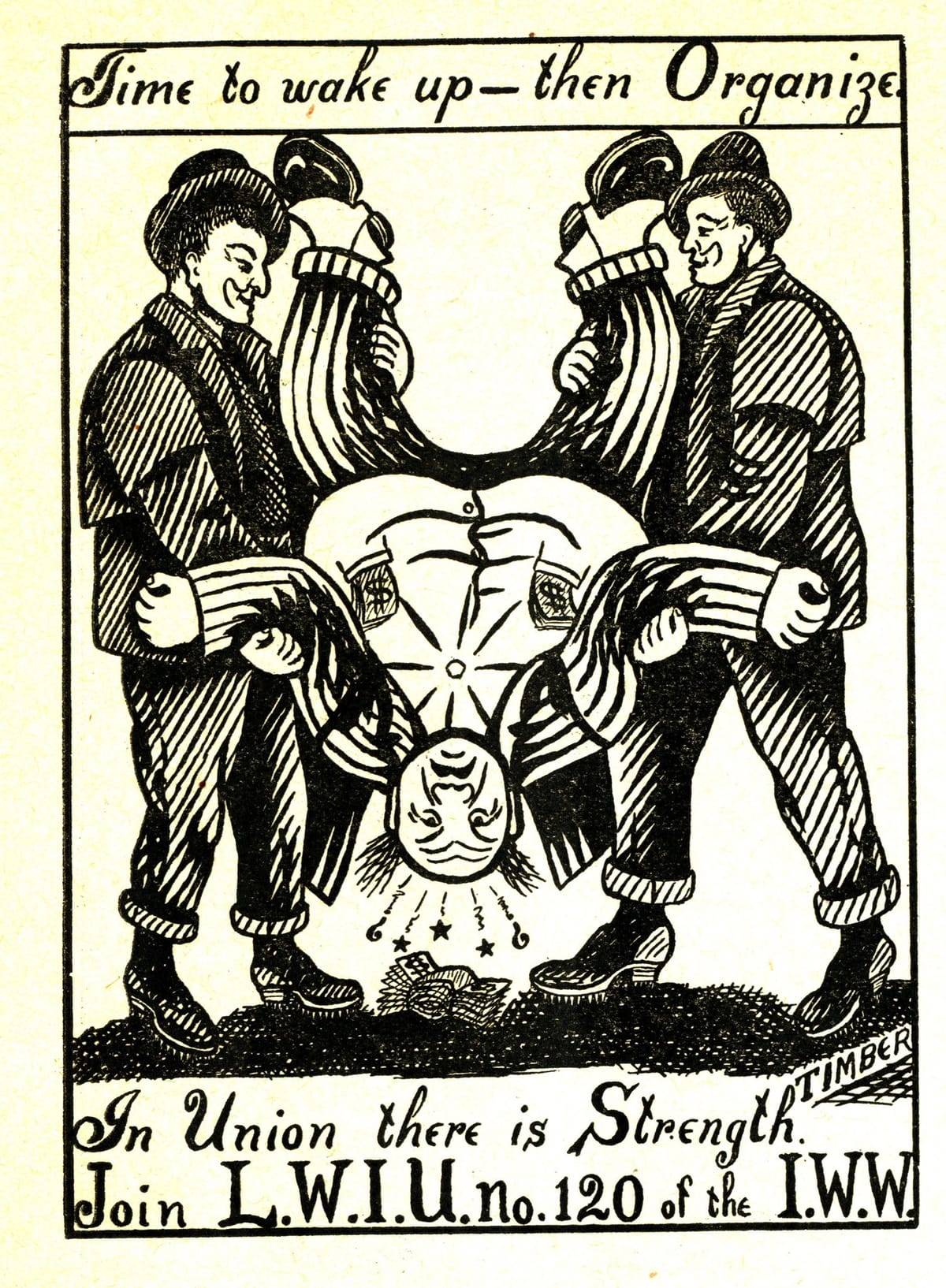

We need a new, revolutionary type of unionism that can confront the power of the employing class. In the second part of this series, we argue that revolutionary unions must build dual power.

This is part two of a series. You can read the introduction to “Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement” here:

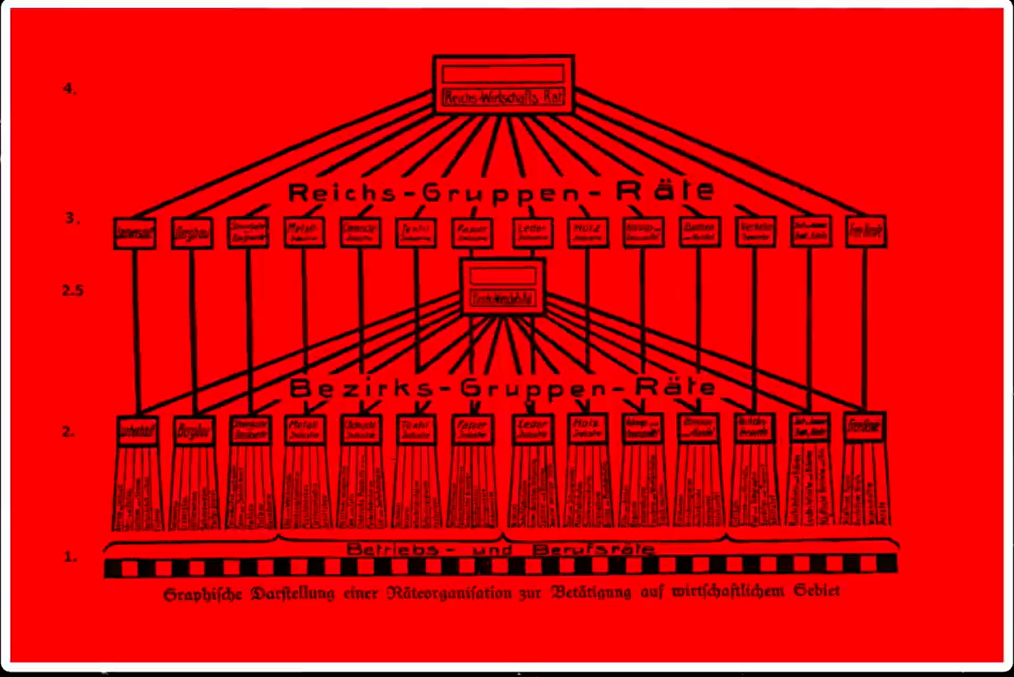

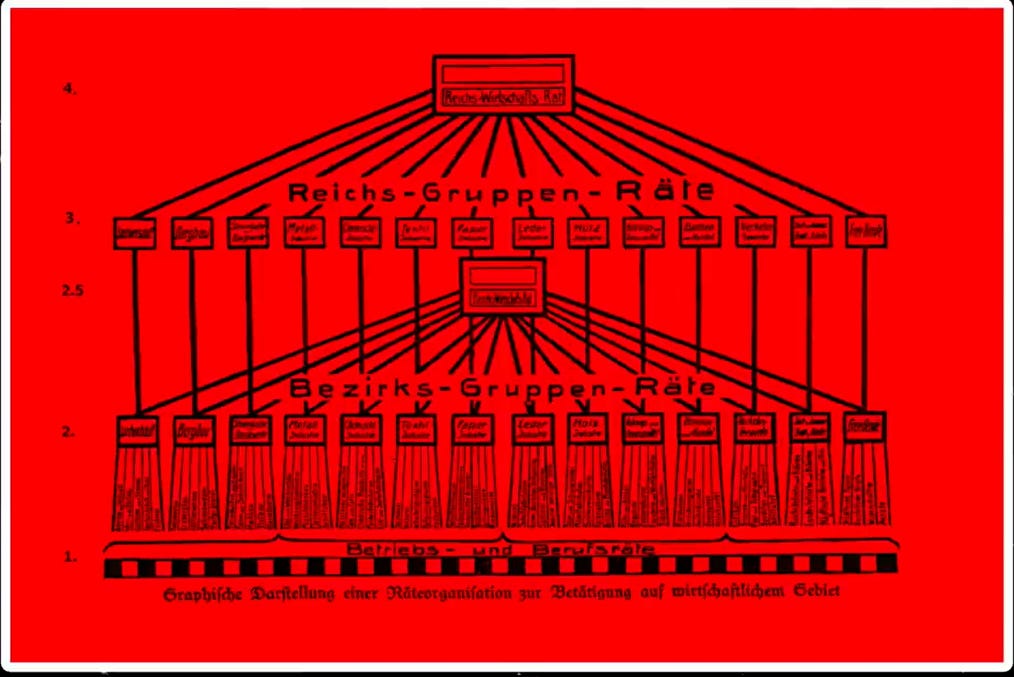

The goal of a revolutionary union movement is to help bring the proletariat to the moment of taking power over society and completing the transition out of capitalism. In other words, a situation of dual power. Originally coined by Lenin to describe the period between the February and October Revolutions when the moderate Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet struggled for control of the state, it has informed every generation of revolutionaries since. A revolutionary union movement helps create a revolutionary counter-power to the capitalist class. One that ends with its final overthrow. We are the ones who will lead the expropriation of the means of production from the capitalists. Afterwards, the revolutionary union movement will become the organizational expression of workers' self-management of production and social reproduction in all industries and workplaces. Democracy would finally extend into the economy, with all production serving society as a whole rather than a few at the top.

Our task during a moment of revolutionary rupture is the conquest of the means of production, globally. No other fundamental, revolutionary transformation of society is possible without this happening. The revolution will wither and eventually die. Worker control over production gives the people the leverage to force the authorities to obey us. During the Russian Revolution, the Provisional Government did “not possess any real power, and its directives are only carried out to the extent that it is permitted by the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, which enjoys all the essential elements of power, since the troops, the railroads, the post, and the telegraph are all in its hands”. By controlling key sites of production and logistics, the soviets could flex political power enforced by the large number of soldiers who’d defected to the revolution.

This brought the workers’ council—an independent, directly democratic, working class institution for economic and political decision-making—onto the world stage. Workers’ councils proliferated across the Russian Empire, Germany, and much of the rest of the world between 1917 and 1927. Workers’ councils also spawned numerous militias that could fight to defend revolutionary gains. Revolutionary unions must be able to lay the infrastructure for the rapid spread of workers’ councils and popular assemblies in a situation of Dual Power.

As workers occupy their workplaces and begin to run them, a tension between socialization and nationalization will emerge. Using the state to take over and plan production to meet society’s needs seems like the quickest way to begin building a new economic system. But the experience of the proletariat during the Russian and German Revolutions should caution us against this. Writing in 1930, the Kollektivarbeit der Gruppe Internationaler Kommunisten (GIK) reflected on the legacy of the Russian Revolution in a text titled “The Workers Councils as Organisational Foundation of Communist Production”. The Bolsheviks, facing economic chaos and counter-revolution, used the coercive power of the state to wrest “the day to day management” of industries from the workers’ councils with the Decree on Workers’ Control. This decision “embroiled” them “in contradictions with the masses of workers” that deformed the process of socialist construction. It led them down a pathway that departed from their own Marxist analytical foundation. Friedrich Engels made this clear in Anti-Dühring:

The modern state, whatever its form, is an essentially capitalist machine, the state of the capitalists, the ideal aggregate capitalist. The more productive forces it takes over into its possession, the more it becomes a real aggregate capitalist, the more citizens it exploits. The workers remain wage workers, proletarians. The capitalist relationship is not abolished, rather it is pushed to the limit...State ownership of the productive forces is not the solution of the conflict...This solution can only consist in actually recognising the social nature of the modern productive forces, and in therefore bringing the mode of production, appropriation and exchange into harmony with the social character of the means of production. This can only be brought about by society's openly and straightforwardly taking possession of the productive forces, which have outgrown all guidance other than that of society itself.

Wage labor and commodity production continued under the USSR. Its product was somewhat more evenly distributed than in capitalist societies through the machinery of government. People did not have to worry about unemployment or homelessness, and had access to broad social benefits like free healthcare and education. But that does not change the fact that nationalization in the USSR failed to fundamentally change the relations of production. Worker autonomy is integral to socialism.

Lenin himself recognized—in both State and Revolution and “The Dual Power”—that the state machinery under capitalism cannot be copied and pasted to implement socialism. He looked to the example of the Paris Commune as a model. That “essence of the Paris Commune as a special type of state” meant that power was “based…on the direct initiative of the people from below, and not a law enacted by a centralised state power.” Dual power required “the replacement of the police and army, which are institutions divorced from the people and set against the people, by the direct arming of the whole people.” Workers and peasants would replace the basis of the “officialdom, the bureaucracy” with “the direct rule of the people themselves or at least placed under special control…subject to recall at the people’s first demand.”

This Lenin had seemingly vanished under the stresses of the Russian Civil War. His fixation on the state machinery led him to adopt practices that diminished the liberatory potential of the Russian Revolution, regardless of his personal intentions. We must also acknowledge the nearly impossible situation he and the Bolsheviks faced after the October Revolution. The failure of the German Revolution in 1918 and 1919 loomed large over the early Soviet Union. Cut off from the industrial heartland of Western and Central Europe, the Soviets had to go it alone. While the Russian Empire had some of the most advanced industrial enterprises concentrated in its cities, its place in the capitalist world system of the time relegated the vast majority of its population and territory to suffer under an underdeveloped, semi-feudal agrarian economy. Later revolutionary upsurge in the Global North—whether Anarchist, Marxist-Leninist, Maoist, Autonomist or whatever—also failed. Faced with a (mostly) united NATO bloc led by the US, survival was an immediate and overriding need. Building socialism in such circumstances is a nightmare. Of course it all failed. Our proletarian revolution can only be global, or it will not be.

History also shows us that nationalization can co-exist with capitalism fairly easily. Most capitalist countries have nationalized one or more of their industries over time, especially during the Postwar Period, when employers needed to make concessions to avoid revolution. In addition, nationalization retains the hierarchies of capitalist production, except that workers and management now report to an “aggregate capitalist” in the form of the state. Under Neoliberalism, the working class has witnessed how swiftly governments can privatize whole industries, such as the railroads in the UK, public education in the US, and state-owned mining companies in the Ukraine. In the USSR, the transition back to capitalism was as simple as selling off all the industries to mobsters and the former Communist Party officials who had once managed them. This disastrous privatization is the origin of Putin and Russia’s famous oligarchs. Nationalization, then, is not enough to dismantle the capitalist relations of production.

Nationalization is still preferable to private ownership. If the state represents an “aggregate capitalist,” it reduces the number of enemies we face in a revolutionary upheaval. A revolutionary union movement, then, could resolve the contradiction between socialization and nationalization by expropriating the public sector itself. Public sector workers would seize the socially beneficial elements of the state so it can be governed directly by workers and community members working together democratically. Meanwhile, the revolutionary unions would smother the violent and authoritarian parts of the state—such as the prison-industrial and military-industrial complexes.

The best tool the revolutionary unions have to invoke this state of dual power is the general strike. A general strike is when most, or all, workers in an industry or geographic location refuse to work until their demands are met. General strikes frequently feature insurrections against the police, workplace occupations, and the creation of directly democratic bodies run by and for workers. For example, the Seattle General Strike of 1919 resulted in the working class essentially running the city for the duration of the strike: “The strike was not a simple shutdown of the city. Instead, workers in different trades organized themselves to provide essential services, such as doing hospital laundry, getting milk to babies, collecting wet garbage, and many other things”. Striking workers and their communities understood their actions as preparation to self-manage the economy and society. Their idea of what the 1917 Russian Revolution stood for inspired them to try and spread what was still an international working class revolution in the wake of WWI.

The Spanish Revolution, coinciding with the Spanish Civil War of 1936-9, represents perhaps the best example of a revolutionary union building dual power and leveraging it during a societal rupture. United with anarchist militants, the CNT, a revolutionary syndicalist Spanish union, through robust worker and peasant organizing spanning decades, defeated Francisco Franco’s fascist coup across much of Spain. Otherwise it’s unlikely the Spanish Republic would have lived at all. These same workers and peasants then, temporarily, built a new society based on confederal communist principles.

But much has changed since 1917-1923, 1936, or 1968. Our challenge today is to map out a strategy that leads to a situation of dual power. A large part of that work is building concrete, autonomous working class institutions. Many formations, both formal and informal, are already engaged in constructing them—labor unions, tenant unions, mutual aid groups, political collectives, and organizations trying to mix these currents like Black Rose Anarchist Federation. We encourage everyone interested in the revolutionary transformation of society to read the first edition of their program, released last year. It impressed seemingly every serious revolutionary organizer who encountered it.

With all that said, we are writing for those who have taken the path of revolutionary union organizing. Where does a revolutionary union fit in this ecosystem? What does a revolutionary union actually look and act like?

Part three is out! Read it here:

Who are the Angry Education Workers?

This is a project to gather a community of revolutionary education workers who want a socialist education system. We want to become a platform for educators of all backgrounds and job roles to share workers’ inquiries, stories of collective action, labor strategy, theoretical reflection, and art.

Whether you’re interested in joining the project, or just submitting something you want to get out there, get in touch! All levels of involvement are welcome. Burnout culture is bullshit.

Reach out to angryeducationworkers@protonmail.com or over any of our social media. You can also contact us on the signal by reaching out to proletarianpedagogue.82.

Support Our Work

All of our work is freely available, but if you like what we do and want to support us, please consider throwing a little donation our way! It helps us cover the costs of printing, hosting webpages, and supplies.